Represent

I was just thinking that it's probably good, in the context of this image-soaked culture, that there's nothing to see here at my journal.

So writes John, whose accusation of picture-thinking is pretty clearly aimed at Fort Kant. Maybe the core of John's objection could be put this way: what's most knowable to us is not what's most knowable in itself.

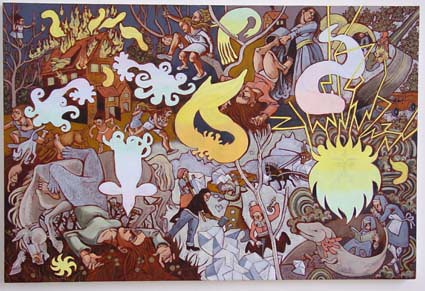

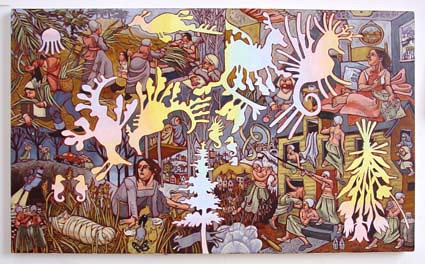

To further this discussion, Fort Kant, which strives to be knowable to us, offers moving images—the excellent and violent Flash animations of Justin Canha, a young teenager from New Jersey. His story might matter to your understanding of his work, though it might not matter at all, for the actions depicted in these movies are pretty much universally intelligible, if anything is.

So writes John, whose accusation of picture-thinking is pretty clearly aimed at Fort Kant. Maybe the core of John's objection could be put this way: what's most knowable to us is not what's most knowable in itself.

To further this discussion, Fort Kant, which strives to be knowable to us, offers moving images—the excellent and violent Flash animations of Justin Canha, a young teenager from New Jersey. His story might matter to your understanding of his work, though it might not matter at all, for the actions depicted in these movies are pretty much universally intelligible, if anything is.